The day dawns, May 7, 1823. From the second floor of his house, converted into an observatory amateur, Heinrich Olbers puts the finishing touches on the article with which he will leave his name in history. That historic night ended with a magnificent sunrise, and led to the revelation of a paradox. This paradox, which others have pointed out before, will captivate generations of researchers and neophytes (including the poet Edgar Allan Poe) for centuries to come. Why are the nights dark if there are an infinite number of stars?

The loss of infinity

The vision of an eternal and unlimited universe, shared by Olbers and his contemporaries, implied that the sky should be populated by an also infinite sea of stars. But on that happy morning Olbers realized that, faced with infinite stars, it does not matter in which direction we point our eyes or telescopes: our gaze will always intercept one of them.

Olbers, who had ceased his work as an ophthalmologist in 1820 to dedicate himself exclusively to astronomy, posed to the scientific community, on May 7, 1823, the exciting paradox that bears his name. He posits that the cosmological model of the time suggested that every point in the sky should be as bright as the surface of the sun. The night, therefore, would not be dark. Every time we look at the sky we should be blinded by the light of the infinite sea of stars.

In search of explanations

Olbers looked for reasons why this doesn’t happen. He proposed that starlight was absorbed by the interstellar dust that it found on its way to Earth, and that the greater the distance that separates us from the star, the greater the absorption would be.

But astronomer John Herschel shot down the argument. Herschel showed that any absorbing medium filling interstellar space would eventually heat up and re-radiate the received light. Therefore, the sky would continue to be luminous.

The scientific community left the paradox posed by Heinrich Olbers unresolved until his last breath at the age of 81, on March 2, 1840.

Many stars and galaxies on a dark background, according to JWST images. E. SA/Webb, NASA & CSA, A. Martel, CC BY

An enigma to Edgar Allan Poe

Eight years later, on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, on February 3, 1848, Edgar Allan Poe, famous after the publication of The Ravenpresented his Cosmogony of the Universe in

the New York Society Library (as he did with his poem Eureka). Poe was convinced that he had solved the enigma popularized by Olbers, as he claimed in his correspondence.

To begin with, Poe proposed, unlike the philosopher Immanuel Kant and the mathematical astronomer Pierre-Simon Laplace, that the cosmos had emerged from a single state of matter (“Unity”) that fragmented, and whose remains dispersed under the action of a repulsive force.

The universe would then be limited to a finite sphere of matter. If the finite universe is populated by a small enough number of stars, then there is no reason to find one in every direction we look. The night can be dark again.

Poe also found a solution to the paradox, even if the universe were finite: if we suppose that the extension of matter is infinite, that the universe began at some instant in the past, then the time it takes for light to reach us would limit the volume of the observable universe.

This time interval would constitute a horizon beyond which distant stars would remain inaccessible, even to our most powerful telescopes.

Edgar Allan Poe died a year later, on October 7, 1849, at the age of 40, without knowing that his intuitions solved the scientific enigma of the dark night sky more than a century after he posed them.

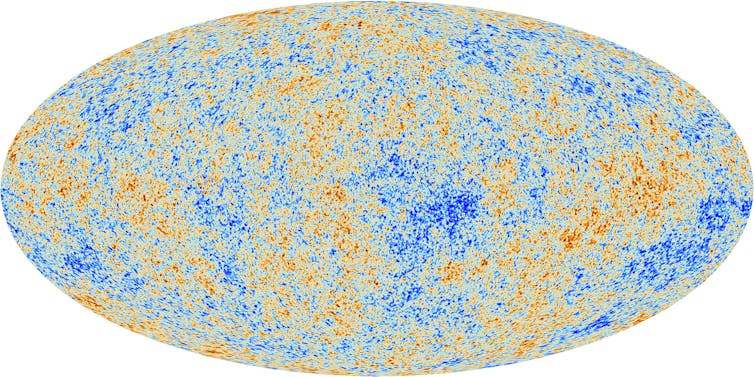

Planck Mission: The most detailed image in history of cosmic background radiation: the remains of the Big Bang. Planck Collaboration / ESA, CC BY

The “two and a half facts” to explain the cosmos

In the interwar period, multiple theories of the cosmos emerged, based on Einstein’s general relativity. Furthermore, the field of cosmology, until then largely reserved for metaphysicians and philosophers, began to be tested by observations. According to radio astronomer Peter Scheuer, cosmology in 1963 was based on only “two and a half facts”:

- Fact 1: The night sky is dark, something that has always been known.

- Fact 2: galaxies are moving away from each other, as Georges Lemaître intuited and as Hubble’s observations, published in 1929, showed.

- Fact 2.5: The contents of the universe are probably evolving as cosmic time unfolds.

The interpretation of facts 2 and 2.5 aroused great controversy in the scientific community in the 1950s and 1960s. Supporters of the stationary model of the universe and supporters of the model of the big bang They admitted, however, that whatever the correct model was it had to explain the darkness of the night sky.

Cosmologist Edward Harrison resolved the conflict in 1964.

May the paradox rest in peace

From the Rutherford High Energy Laboratory near Oxford, Harrison showed that the number of stars in the observable universe is finite. Although they are very numerous, they are formed in limited quantities from the gas contained in galaxies. This limited number, combined with the gigantic volume that today covers the matter of the universe, causes darkness to manifest between the stars.

In the 1980s astronomers confirmed the resolution proposed by Poe, Kelvin and Harrison. Some, like Paul Wesson, even expressed the wish that Olbers’s paradox would finally rest in peace.

In the middle of a dense forest, tree trunks can be seen in all directions. Pxhere, CC BY

A sky twice as bright beyond Pluto

But good paradoxes never completely die.

Recent measurements by the New Horizons probe, in an orbit beyond Pluto and beyond the dust of the inner solar system, indicate that the sky is twice as bright as we predict based on stars alone. This time, either there are missing stars or there is light that we do not see. Is this a new cosmic background?

The question of the darkness of the sky therefore remains valid, and is of great scientific relevance, 200 years after Olbers first considered the darkness of the night and the infinite stars.

Alberto Domínguez, Astrophysics Researcher, Complutense University of Madrid; David Valls-Gabaud, Astrophysicist, Research Director at CNRS, Paris Observatory; Hervé Dole, Astrophysicist, Professor, Vice-President, art, culture, science and society, Paris-Saclay University; Jonathan Biteau, Lecturer in astroparticle physics, Paris-Saclay University; José Fonseca, Assistant Research, University of Porto; Juan Garcia-Bellido, Professor of Theoretical Physics, Autonomous University of Madrid y Simon Driver, ARC Laureate Fellow and Winthrop Research Professor at the International Centre for Radio Astronomy Research, UWA., The University of Western Australia

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original.