The unique device attracted curious eyes everywhere. From the outside it looks like a big black box on a tripod but the real magic is inside. It is a handmade wooden camera and darkroom.

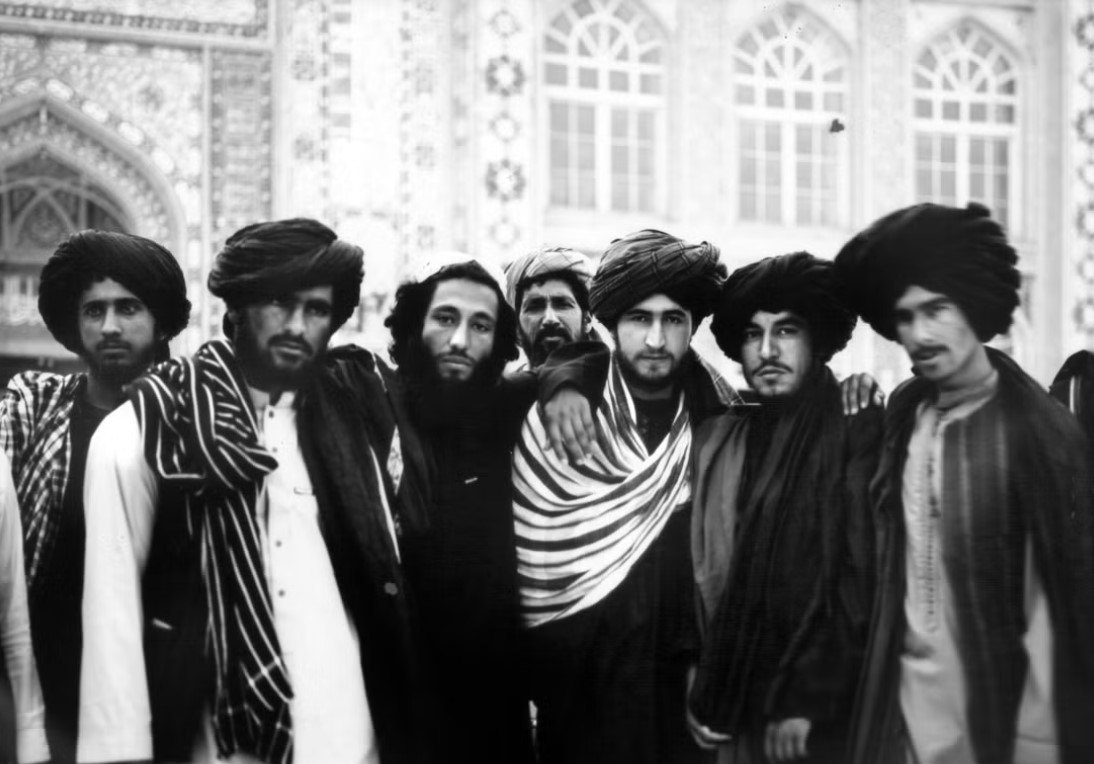

As a small crowd gathers around the box camera captures images of a life full of beauty and hardship from its dark interior. .

Other images include children laboring in a brick kiln, women in burqas and armed youths with flames in their eyes.

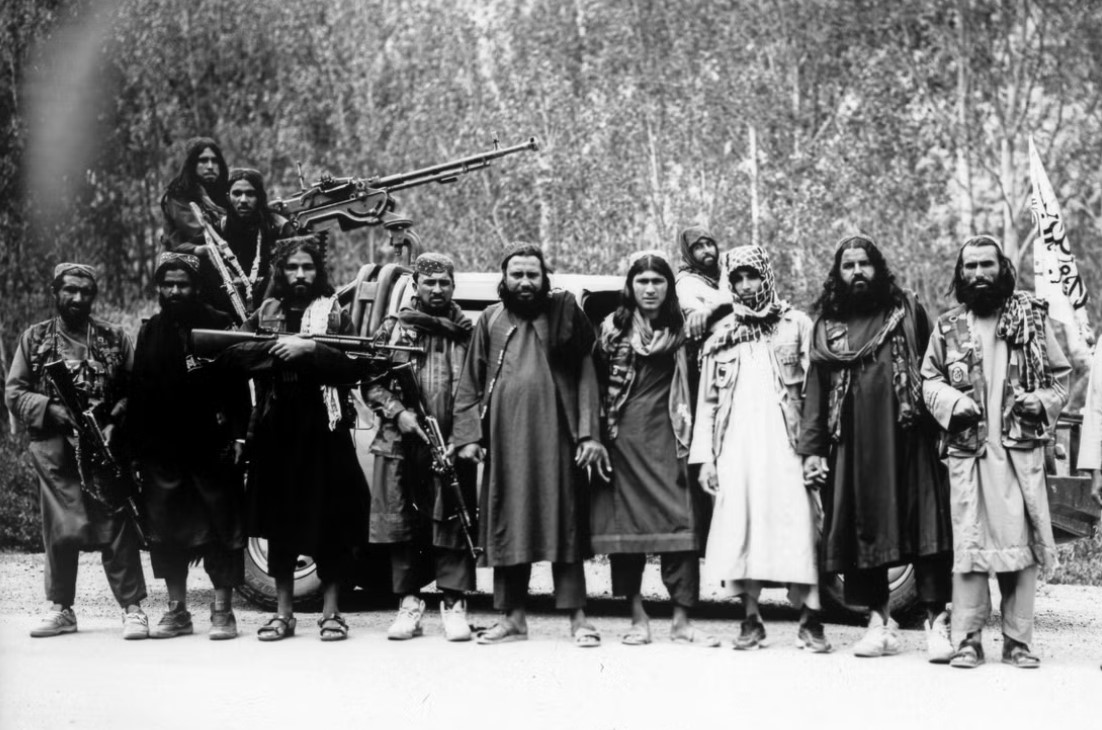

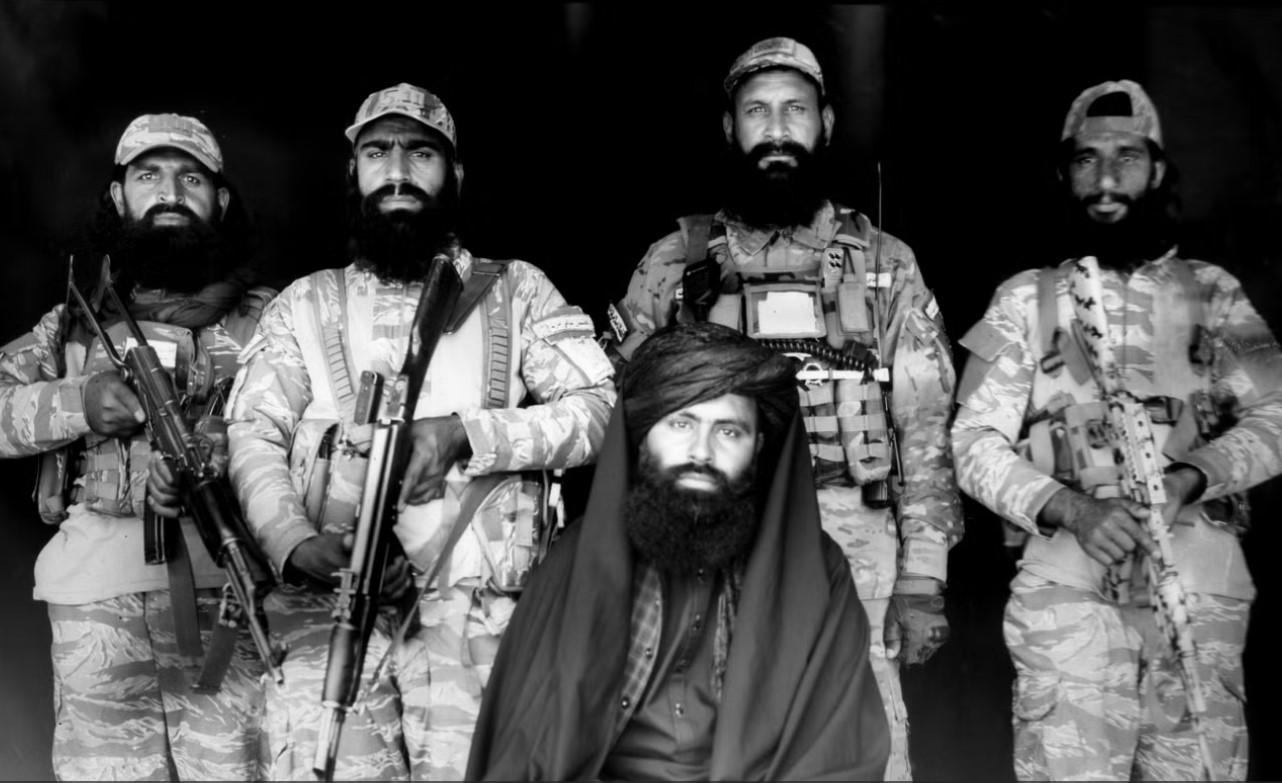

A Taliban fighter posing for a portrait in a war-torn Afghan village says: ‘Life is much happier now.’ But life is the opposite for a young woman in the Afghan capital, Kabul, who has been denied an education because of her gender.

He says, ‘My life is like a prisoner, like a caged bird.’

The device used to record these moments is called ‘camera instant’ here. In the last century, these cameras were common on the streets of Afghan cities as a quick and easy way to create portraits, especially for identification documents. They were simple, cheap and portable.

These cameras have captured the country’s dramatic transformations for half a century, from monarchy to communist takeover and foreign invasion to insurgency, but have been rendered obsolete by 21st-century digital technology.

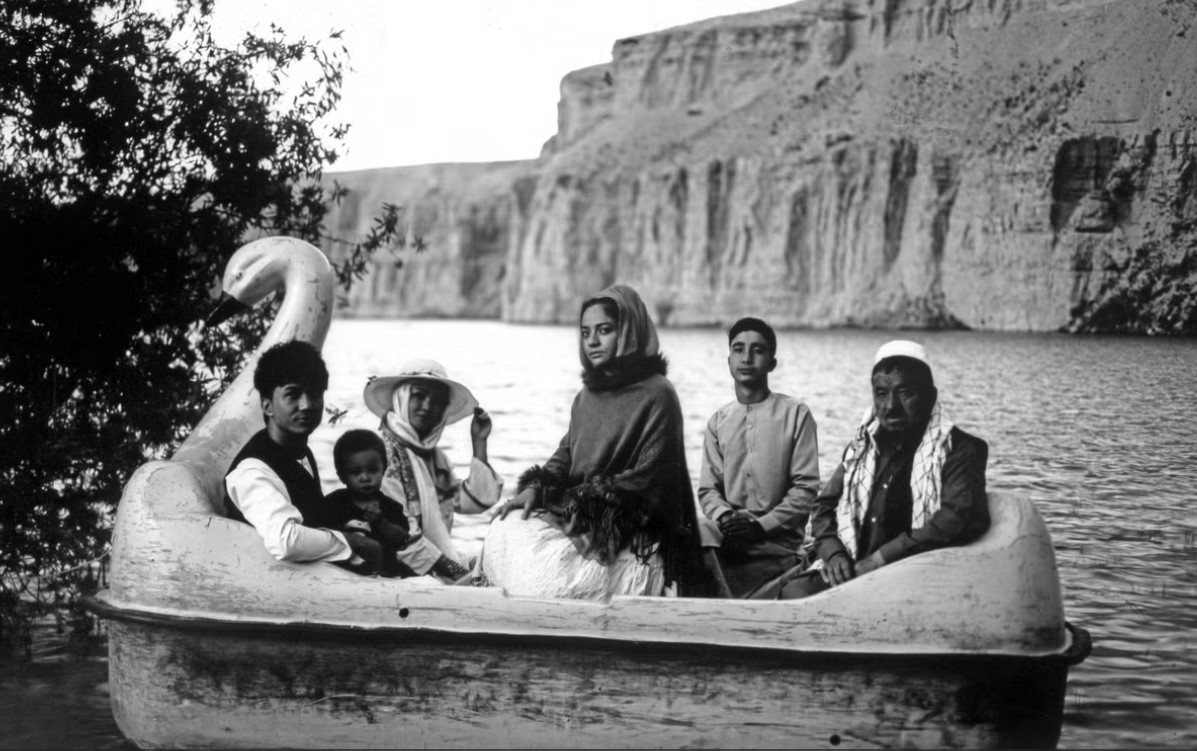

From Herat and Kandahar to Kabul and Bamiyan, hundreds of black-and-white photographs have been made using these almost extinct cameras to document life in post-war Afghanistan, revealing a complex and sometimes conflicting narrative. are

The photos, taken over the course of a month, show how life has changed dramatically for many Afghans two years after the withdrawal of US troops and the Taliban’s return to power, and for others, decades. Little has changed over the years, regardless of who has been in power.

Pictures taken with a bygone device, the box camera, show that the country’s past still dominates its present in some respects, which it does.

At first glance, the blurred, black-and-white and out-of-focus images depict an Afghanistan where time has stood still. But this is an aesthetic deception. They are a reflection of the country as it is now.

Afghans’ uneasy relationship with the camera

During their first term in power from 1996 to 2001, the Taliban banned depictions of humans and animals that were against the teachings of Islam.

Many box cameras were broken at this time although some were quietly tolerated. But the advent of the digital age proved to be the last nail in the coffin of this device.

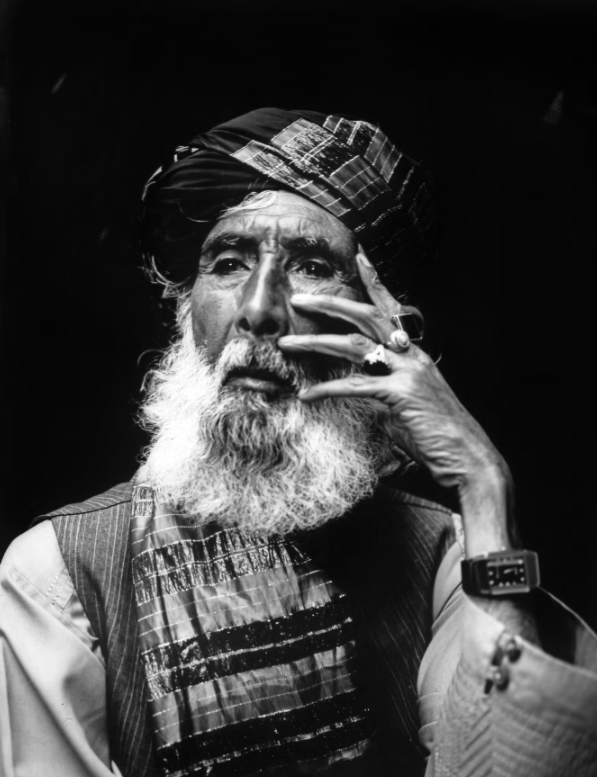

“These things are gone,” says Lutfullah Habibzada, 72, a former photographer for Camera Four in Kabul. Digital cameras are on the market and (the old ones) have become obsolete.’

Habibzada still has his old box camera that was given to him by his father, a noted photographer in the last century.

It no longer works, but they have lovingly preserved its red leather coating, which is emblazoned with photographs taken of it.

Today, faces are spray-painted on advertising billboards on the streets of Afghan cities, and statues’ heads are wrapped in black plastic bags to comply with a new ban on face photography in clothing stores.

But the internet age and the advent of smart phones have made it impossible to ban photography. The new look of an old box camera arouses excitement and curiosity even among those who abide by the new strict rules. Many Taliban, from foot soldiers to high-ranking officials, were happy to pose for box camera portraits.

A crowd of men stare intently as a camera sets up outside a warehouse in Kabul. At first they seem shy, but as the first portraits are revealed, curiosity overcomes their reservations. Soon they are smiling and joking with each other.

They are also willing to help when a black cloth backdrop has to be put up against the wall while waiting for photos to be taken. Stern faces replace fleeting smiles as everyone moves forward for their photo. Adjusting their grips on their assault rifles, they look straight into the camera’s tiny lens and strike a pose.

Most of them joined the Taliban in their teens or early 20s and have known nothing but war. He was drawn to the radical movement by his fervent faith and determination to expel US and NATO troops invading his country, who had propped up two decades of corrupt and criminal Afghan governments. Fail to control.

Bahadur Rahani, a 52-year-old Taliban member with pale blue eyes peeking out from under a black turban, says he is happy to see the Taliban back in power. According to him, ‘Afghanistan will be reconstructed and it is not possible without the Taliban.’

Peace, which has a heavy price

Two years after the Taliban regained control of power across the country, there are strong echoes of life as it was before the government was toppled by US-led NATO forces in 2001.

The country is once again ruled by a radical movement that has reinstated many of the draconian laws it had imposed. The first Taliban government in the 1990s was notorious for destroying art and culture deemed un-Islamic, such as the bombing of a large and ancient Buddha statue carved into the mountains in Bamyan.

They imposed brutal punishments, cut off the hands of thieves, hanged insolents in public squares and stoned women for ‘adultery’.

This time also the punishments of hanging and flogging have been imposed. Music, films, dance and performance are banned and women are once again excluded from almost all public life, including education and a few professions.

The return to radical policies has forced Western donors, aid workers and trading partners to pull back. Poverty has reached crisis levels due to bans on women working, cuts in foreign aid and international sanctions.

But it is a relief that the continuous bloodshed of the last four decades of invasions, multiple insurgencies and civil wars has largely ended.

There are still occasional bombings, mostly blamed on the anti-Taliban militant group Daesh Khorasan, but most Afghans interviewed say their country is the most peaceful it has been in decades. Is.

According to the UN report, 1095 civilians were killed in deliberate attacks between August 15, 2021 and May 30, 2023. This is the period when the Taliban regained power. Those who dislike the current government say that robberies, kidnappings and corruption, which were rampant under previous governments, have been largely curbed.

But less crime and less violence are not necessarily substitutes for prosperity and happiness.

Women disappear from the scene

In a three-story building on a street in Kabul, a group of women quietly work on a khadi. Emerald’s hands move quickly, her nimble fingers twirling the threads of yarn as she knots the colorful wool into a carpet. She works as fast as a machine, but her voice is soft and sad.

He said: ‘My life is like a prisoner. Like a bird in a cage.’

Another 20-year-old woman was studying computer science, but the Taliban banned women from attending universities before she graduated. Now she and her 23-year-old sister work in a carpet factory, practicing the skills their mother taught them as children. She is one of the very few women who can earn money outside the home and like others, she has not disclosed her full name.

Among the biggest changes women have faced since the return of the Taliban is clothing. They have strict dress codes, are barred from most jobs for women and are denied even small pleasures like going to the park or going to a restaurant.

Girls cannot go to school beyond the sixth grade and women need a mahram to travel.

For all these ambitions and objectives of the Taliban, women are being erased from public life.

Even in this environment, Zamarud did not give up on his dream of graduation, saying, ‘We have to have hope. We hope that one day we will be free and we live and breathe in the hope that freedom is possible.’

In another room, 50-year-old Hakima is teaching her teenage daughter Ferishta the art of weaving. It is the only way for her to earn a living although she still dreams that her 16-year-old daughter will one day become a doctor.

Hakimiya says that ‘Afghanistan has gone backwards. They have to wear the full burqa to make a picture. People go door to door begging for a piece of bread because our children are starving.’

While economic freedom and women’s voice in public life and government have turned back the clock in conservative, tribal parts of the country, expectations for women in Afghanistan have always been different and have changed little over the years. Even during the presence of US and NATO troops.

This section contains related reference points (Related Nodes field).

Yet education remains a priority for many Afghans. In dozens of interviews across the country, almost everyone, including some Taliban members, said they wanted girls and women to be educated. Most said they believed the education ban was temporary and that older girls would eventually be allowed to return to school. They say that keeping girls and women under house arrest does not benefit the country or its economy.

Haji Mohibullah, a 34-year-old teacher from a village in Kandahar says, “We need doctors, teachers.” Women should be educated so that Afghanistan can improve in every field.’

The international community has not recognized the Taliban government and has pressured its leadership to lift restrictions on women, but to no avail. Taliban government spokesman Zabihullah Mujahid said during an interview in Kandahar: ‘It is up to Afghans, not foreigners, they should not be involved in this matter.’

According to the spokesperson: ‘We are waiting for the right time to open the school. And while schools are closed now, they won’t be forever.’ He did not give a timeline but insisted that “the world should not use this as an excuse not to recognize the Taliban regime.”

Fateh Baghi

The village of Tabin is located in the Arghandab river valley. Isolated from the dusty desert of Kandahar province, it is a fertile patch of orchards and irrigation canals.

But the remnants of war are everywhere around him. Abandoned remnants of American war posts obscure the warnings of landmines and grenades painted on walls bent by blasts. Tangled pieces of abandoned barbed wire are strewn about.

Houses have been reduced to ruins by bombardment and there are armed men everywhere who are struggling to move from a life of combat to a life of peace.

New jobs, overseeing roads, protecting buildings and collecting garbage are essential daily tasks for rulers. It’s less dramatic than waging war, but there’s a distinct sense of calm in the absence of violence.

Without fear of airstrikes or bullets, children jump from a bridge into muddy water and scream with joy in a canal.

Abdul Halim Hilal, 28, hides from the scorching sun under a mulberry tree before posing for a photo: ‘Life is much more enjoyable now. Before that, there used to be a lot of cruelty and aggression. Innocent people died. Villages were bombed. We couldn’t afford it.’

Considering it a moral duty to fight foreign soldiers, he joined the Taliban as a teenager. He lost more than 20 friends in the war and even more were injured. When they see the orphaned children, they are overwhelmed by the memory of their dead brothers but are comforted by an unshakable belief that their sacrifice was worth it.

He says: ‘Those who were killed were fighting to sacrifice themselves for the country. It is because of their blood that we are here now, giving free interviews and the Muslims here are living in peace.’

A villager walks by, noticing the flurry of curious children and adults gathered around the box camera. ‘It’s so weird’, he mutters. ‘We used to fight against these foreigners and now they are here taking pictures.’

26-year-old Taliban fighter Mujibur Rahman Faqir now manages a security post in Kabul. Like many others, they are struggling to adapt to peacetime thinking because they have only known war. According to him: ‘I was ready to sacrifice my head and I am still ready.’

A shaky economy and a struggle to survive

Since the end of the war against the American forces, the security situation in Afghanistan has improved, but along with the peace, the country is also facing economic decline.

When the Taliban regained power in 2021, international donors withdrew funding, froze Afghan assets abroad, isolated its financial sector and imposed economic sanctions on the country.

An almost total ban on women working has further crippled the declining economy. According to the United Nations Development Program, per capita income decreased by an estimated 30 percent last year compared to 2020.

The United Nations World Food Program says that nearly half of Afghanistan’s 40 million people face severe food insecurity. In 25 out of 34 provinces, malnutrition has gone above the emergency threshold.

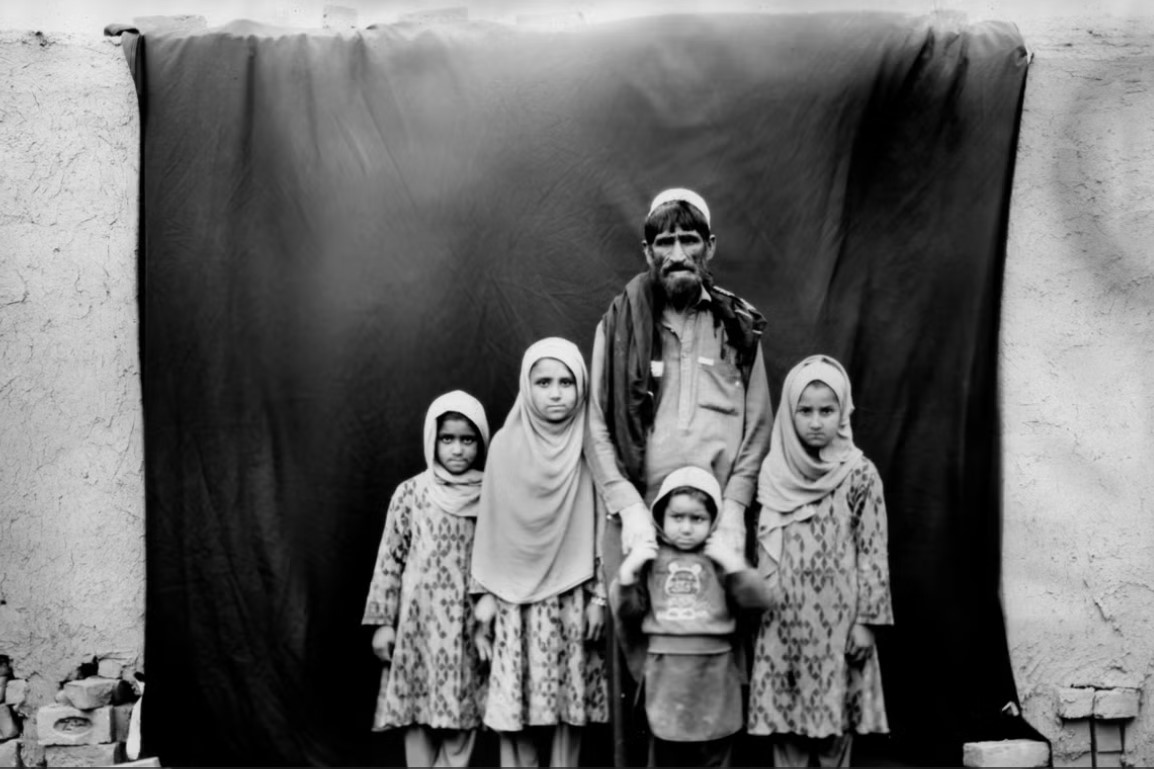

Struggling to survive is something Kasanya has learned since she was four years old. In a brick kiln outside Kabul, she scoops out a lump of clay with her tiny hands, kneading it until it becomes pliable for a brick mold. After doing this countless times, his hands start moving automatically.

She works from sunrise to sunset six days a week, with short breaks for breakfast and lunch. Along with her siblings and her father, she works like many families in this sprawling factory where children become laborers at the age of three.

Waheedullah, 35, Kasanya’s father, says that everyone wants their children to study and become teachers, doctors and engineers and shape the future of the country.

According to him, even with the whole family working, there is often no money for food and they survive by taking loans from shopkeepers. Of his three sons and three daughters, all but the youngest work as brickmakers.

Waheedullah said, “When I was young, I dreamed of living a comfortable life, having a nice office, a nice car, going to parks, traveling around my country and abroad, and going to Europe, but instead I got bricks.” I make it.’ There was no bitterness in his voice, just acceptance of an inevitable fate.

Many Afghans are forced to sell their own goods to make ends meet. From furniture to clothes and shoes.

When the Taliban banned the films, Nabi Attai had nothing to fall back on. He appeared in a dozen television series and 76 films as an actor in the 70s, including the Golden Globe-winning 2003 film Osama. But now they are helpless.

His house is in a low-lying street that is now almost empty of furniture that he sold in the market to support his family. Household items sold include those favorite TVs.

Nabi Attai has no work after 42 years of acting. Neither have their two sons who were part of the film and music business. Attai is happy that the roads are now safe, but he has to feed his family of 13, but there is no way to feed them.

They have requested the local authorities for anything from garbage collection but there was nothing. So they had no choice but to sell their goods.

According to Attai: ‘I have no hope yet. Under the Taliban’s laws, begging is now punishable by imprisonment.

For the past one year, he has become weak. His cheeks are sunken, his body shriveled. There is a sadness in his eyes that rarely fades even when he recounts his glory days.

He said: ‘We have made good films before. For God’s sake, music and cinema will be allowed again and people will join hands to rebuild the country so that the government will come closer to the people and embrace each other as friends and brothers.’

A little flash of glamour

When night falls in Kabul, the twinkling lights of wedding halls dispel the darkness. It’s a little flash of glamour.

Despite the economic downturn, the business of marriage halls is flourishing. As the security situation improves, some wealthy Afghan refugees are returning home for traditional wedding ceremonies. Weddings are a big part of Afghan culture and families sometimes go to great lengths to ensure a lavish party for hundreds or thousands of guests.

The construction of the Imperial Continental Wedding Hall started four years ago but was interrupted due to the Corona epidemic and the Taliban taking over. The magnificent banquet hall finally opened its doors last year.

The Continental’s 30-year-old manager, Muhammad Vasil Qawani, in a lavish suit, roams the glamorous and interconnected halls where four weddings were held in one night. He is a former lecturer in economics and politics at Kabul University who is trying to ensure business growth despite the country’s economic woes. But it is not easy.

He says: ‘Businesses are vulnerable and strict government regulations are not helping. The Taliban are raising taxes.’ But they say there isn’t enough business to support a better tax base.

Mohammad Vasil Qawani further said that banning music and dance does not help. Musicians and even DJs ended up being sources of extra income. Marriages are segregated by gender, but sometimes marriages are a bit more hectic for women.

Occasionally women and girls enjoy music on tape in the women’s section of the hall. He said that if they want to do it, they do it whether there are restrictions or not. Women are women.’

On the outskirts of the city of Herat, five hundred miles west of the capital Kabul, 39-year-old businessman Abdul Khaliq Khudadadi faces a different set of challenges.

He is vice president of the Ryan Saffron Company, which exports valuable saffron to overseas customers, particularly in Europe and the United States, but since the Taliban came to power and the resulting sanctions, many foreign clients have switched with the Afghan company. has stopped doing business even though it is one of the few big companies.

Women are still allowed to be employed here, whose delicate hands are considered better suited than men to extract and handle the precious spice from the saffron flowers.

The global embargo on the banking sector has left many Afghan companies with no way to do business with the option of operating through a third country, usually Pakistan, but this increases costs significantly. Then there is the drought which has destroyed many crops including saffron.

His company aimed to increase production this year. Instead, their production has halved compared to three years ago. Khudadadi says she is determined to persevere. For them, a successful business can be the best way to heal Afghanistan’s wounds.

They say that in the early days of chaos after the Taliban came to power, the Khudadadi family also felt intense pressure to join the tens of thousands of people fleeing the country. He had a visa and family and friends encouraged him to leave but he refused.

According to him: ‘It was a very difficult decision but if I go, all the talented, educated people go, who will manage this country? When will the problems of this country be solved?’

#extinct #camera #captured #vicissitudes #Afghanistan

2024-05-07 08:55:54