In 1958, 17-year-old Rose Dugdale was one of 1,400 young women to bow before Queen Elizabeth II at the most prestigious event of the summer debutante season. It was the last time the well-bred daughters of the country’s most aristocratic and wealthy families would be presented to the monarch in a ritual that dates back 200 years. Princess Margaret, with characteristic elegance, would later say: “We had to put an end to it. Every whore in London went in.’

For the fiercely independent Rose Dugdale the presentation to the Queen was a means to an end. She had agreed on the condition that her parents would allow her to attend the all-female St Anne’s College, Oxford, to study philosophy, politics and economics.

Sixty years later he would remember the debutante era as “a horrible marriage market in which women were sold as commodities.” By then, she had traveled a lunar distance from her elite upbringing in rural Devon and London, and the extraordinary arc of her volatile life is perhaps most aptly summed up in the title of a recent biography of hers, Heiress, Rebel, Vigilante, Bomber. , Rebel, Avenger, Bomber).

Photo: YouTube

From reluctant debutante to dedicated IRA volunteer

Written by Irish author and journalist Sean O’Driscoll, the book details Dugdale’s unlikely journey from reluctant debutante to committed IRA volunteer, whose daring adventures and dedication to the cause of violent republicanism made headlines around the world.

In January 1974, he took part in the armed hijacking of a helicopter from which milk pails filled with explosives were dropped on an RUC base in Northern Ireland. A few months later, he organized and led a daring art heist in County Wicklow in which 19 works of art, including paintings by Rubens, Goya and Vermeer, were stolen and held for ransom in exchange for the release of IRA prisoners.

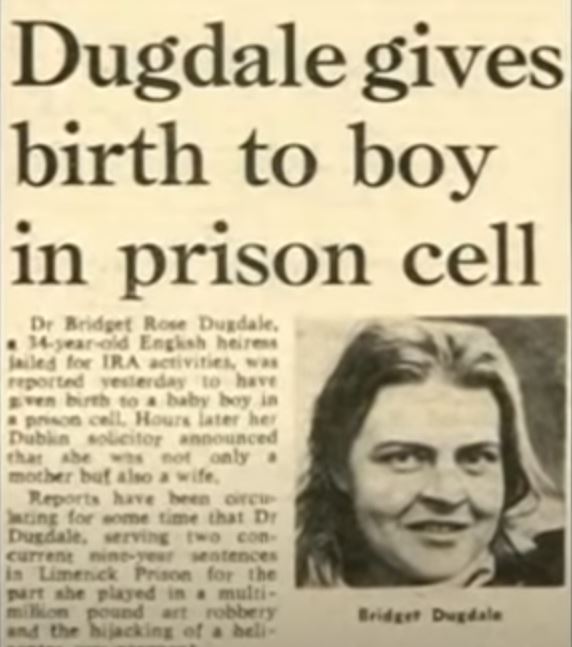

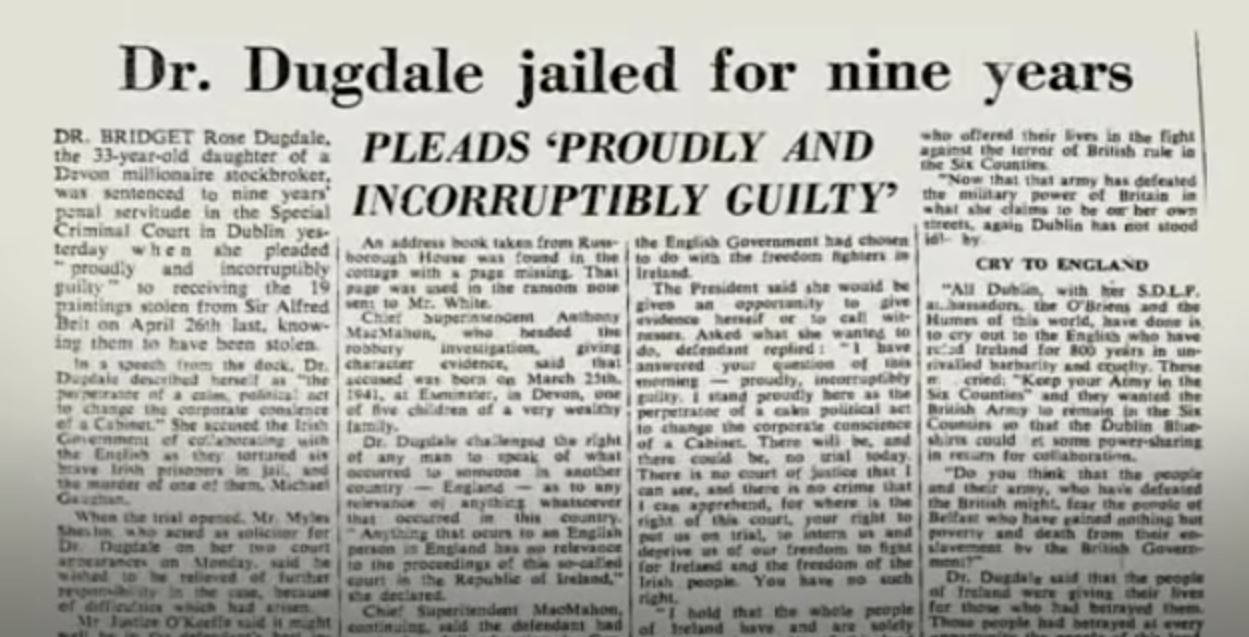

For a time, Dugdale was Britain and Ireland’s most wanted terrorist and a source of gruesome fascination for leaflets. After her arrest, she was tried and sentenced to nine years in prison, having pleaded “proudly and incorruptibly guilty” of crimes against the state. In the dock, he called Britain a “stinking enemy” and gave a fist-pumping salute to the audience.

Photo: YouTube

Along with her partner and accomplice, Jim Monaghan

Unlike other accounts of her exploits that have appeared over the years, O’Driscoll’s book breaks new ground by detailing Dugdale’s post-imprisonment role as a specialist bomb maker for the IRA.

It reveals how, from the mid-1980s to the early 2000s, she and her partner and accomplice, Jim Monaghan, developed a number of deadly improvised devices, including the infamous ‘cookie launcher’. Made from household utensils and pieces of farm machinery, it used biscuit packets to absorb the recoil when an armored missile with semtex explosives was fired. The device was used by the IRA in rural South Armagh and on the streets of west Belfast.

The pair also created a new powerful explosive which was detonated outside the fortified Glenanne Barracks in May 1991, killing three soldiers and seriously injuring 11. The following year, it was used in a bomb which destroyed the Baltic Exchange and surrounding buildings in the City of London , killing three people and causing damage estimated at £800 million. As O’Driscoll believes: “Rose Dugdale didn’t kill anyone directly, but she was indirectly responsible for the deaths of many people.”

Photo: YouTube

“I think it was partly to do with the era in which he came of age.”

As part of his research, O’Driscoll conducted several interviews with the elderly Dugdale in the Dublin nursing home where she now resides. It is run by the “servants of the Mother of God” and is one of the few residents who is not a retired nun.

The book reconstructs her life in some detail, and O’Driscoll has spoken to several of her accomplices and to her son, Ruairi, who she gave birth to while serving a sentence in Limerick Prison. What the book does not do is fully explain why someone so English, privileged, charismatic and intensely intelligent – she wrote her MA thesis on Wittgenstein – embraced Irish democratic violence so fervently.

“I think it was partly to do with the era in which she came of age,” says O’Driscoll. “It is difficult to separate its politics from the actions of other revolutionary groups active in the late 1960s and early 70s – the Baander-Meinhof in Germany or the Red Brigades in Italy. But there is also the bigger question of why she felt she had to go to the lengths she did to prove her radicalism. That answer likely lies in her personal psychology, which is much more difficult territory to explore.”

Watch the trailer for the movie Baltimore

Wild energy and impetuosity

A new feature film titled Baltimore – a reference to a village in County Cork rather than the American city – is an interesting attempt at a psychological portrait of Rose Dugdale.

It focuses mainly on her role in the IRA raid on Russborough House in County Wicklow in 1974, in which the elderly Sir Alfred Beit and his wife were bound and gagged along with their servants, while the 19 elderly masters were stripped of their elaborate frames and were taken to an IRA hideout in west Cork.

Imogen Poots plays Dugdale as a ruthlessly devoted but obsessive person, prone to paranoia and nightmares, but the film’s slow pace fails to capture her wild energy and impetuosity, while elevating atmosphere and submission above any deeper understanding its political motivations.

Photo: YouTube

A different version of herself

“We’ve always been interested in the inner worlds of our characters, more than anything else,” says Christine Molloy, who co-directed the film with her partner Joe Lawlor. “We were drawn to Rose Dugdale because we strongly believed she must be a thinker, and a studied thinker at that. She was also someone who wanted to change her identity. To become a different version of herself.”

The final part of the film focuses on the 10 days Dugdale spent with the stolen paintings in a cottage in a remote area of west Cork before her arrest. Alone, pregnant and perhaps vulnerable, the filmmakers suggest that this must have been a rare moment of reflection for a woman whose life was defined by a lack of danger and risk-taking.

“For an intense period of time, she must have been alone with her thoughts,” suggests Molloy. “What she had begun—on a personal level, as opposed to the events of the art theft itself and the ransom demands—were the steps that ultimately cut her off from her former life: from her family, her home, her country who was born”.

He never regretted it

There is no evidence, however, either in her later interviews or in her continued commitment to the cause, to suggest that Dugdale was in any way remorseful, let alone repentant.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the film has already come under fire from those who feel that any portrayal of a female terrorist, particularly one of such distinguished English parentage, is off limits. A recent article in the Mail on Sunday asked: “Why is a new film celebrating an upper-class debutante from Devon who hijacked a helicopter to drop IRA bombs on an army base?” In this piece, the Daily Mail’s film critic described Baltimore as “a dangerous film … that doesn’t exactly idealize Dugdale, but tries to make her a sympathetic character.”

“For me, the problem was more that, in trying to portray its complexity, the film’s highly imaginative narrative confuses more than it enlightens, while the larger moral questions about the human cost of its unflinching embrace of violence remain meteoric.” writes Sean O’Hagan in Guradian.

Photo: YouTube

Her personal story

Bridget Rose Dugdale was born in March 1941 at Yardie, her father’s 600-acre estate in Devon, her strongly Irish name being abandoned early on in favor of the more iconic English.

The family lived between Devon and London, where they also had a large mansion in Chelsea. Her father, Colonel Eric Dugdale, was an underwriter at Lloyd’s of London, and her mother, Carol, attended the Slade School of Art and was close friends with the writer Rebecca West.

Interestingly, Carol Dugdale’s first marriage was to John Mosley, a stockbroker and younger brother of Oswald Mosley, the notorious British fascist leader. When asked about her young life during an interview for the Irish television series Mná an IRA (Women of the IRA), Dugdale described her parents as “very attentive” and her childhood as “great … with horses and sports and fishing and shooting and all that stuff.’

Photo: nistagrammed / Instagram

“A bit clumsy and masculine”

In a recent op-ed in the Oldie newspaper, however, journalist Virginia Ironside, who attended the same school as Dugdale in Kensington – where she was taught, she recalls, by “strange people with no formal education” – paints a different picture.

Describing her former friend’s upbringing as “obstructingly conventional,” she recalls how, at their mother’s insistence, Rose and her older sister, Caroline, were forced to wear formal clothes and long white gloves to dinner every night and ” they had to bow to every visitor in their house.’

Ironside remembers the young Dugdale as “a little clumsy and masculine – a big girl with a deep voice” who was “not conventionally beautiful, but she exuded such energy, positivity, intelligence, generosity and, yes, even kindness that she was instantly attractive ». He even admits that he had “secretly fallen in love” with her, like many other students, and that he sensed, even at that young age, that she was bisexual.

At Oxford, Dugdale had a passionate affair with a professor named Peter Ady, who had previously been in a relationship with Iris Murdoch, a professor of politics at the college. Years later, as Dugdale languished in Limerick jail, Murdoch, then a respected philosopher and novelist, would write to the Irish ambassador asking that her former pupil be allowed “to receive her books” because she “desires to study but cannot , a terrible additional punishment for an intellectual man.”

In January 1972, television news broadcast disturbing scenes from Derry on what soon became known as Bloody Sunday, where members of the paratrooper regiment killed 13 unarmed protesters. Something changed in Dugdale’s political consciousness

Photo: nistagrammed / Instagram

“Disguised female students storm male-only fortress”

It was at Oxford that Dugdale embraced left-wing politics and first made headlines. In 1961, she and another student, Jenny Grove, disguised themselves as men to attend the all-male Oxford Union debate, where they harassed and berated the speakers in deep, masculine voices.

The intervention made headlines, not least because the couple had alerted a local journalist and photographer to their plan, even inviting them to document their transformation at an Oxford salon. The Daily Express published the report titled “Disguised female students storm male-only fort”.

After graduating, Dugdale went on to earn an MA in philosophy in the US and a PhD in economics at the University of London, before becoming politically active during the tumultuous international protests of 1968.

Rose Dugdale today – Photo: nistagrammed / Instagram

I am selling the house

In 1971, aged 30, she had made the decision to sell her house in Chelsea and donate the wealth she inherited, which O’Driscoll estimates at “well over £1m today”, to the poor and needy of London. To do this, he rented a building in Tottenham and founded a Claimants’ Association, offering advice and financial alms.

“There were a lot of immigrant families coming into the area,” he told O’Driscoll. “I couldn’t overstate how many people were looking for help.”

Throughout her life, Dugdale was attracted to “stray” male would-be rebels such as Eddie Gallagher, a renegade IRA member involved in the helicopter hijacking and art theft, and later Jim Monaghan, her colleague bomber. The first of these was Wally Heaton, a self-proclaimed “revolutionary socialist” with a drinking problem who had been traumatized by the brutality he experienced while serving with the Coldstream Guards in Malaysia. When he turned up at the offices of the Tottenham Claimants Union, preaching violent revolution, the pair began dating. Soon after, at his urging, her attention turned to the unrest in Northern Ireland.

“A turning point – a defining moment of her militancy”

In January 1972, television news broadcast disturbing scenes from Derry on what soon became known as Bloody Sunday, where members of the paratrooper regiment killed 13 unarmed protesters. Something changed in Dugdale’s political consciousness.

Both O’Driscoll and the directors of “Baltimore” identify Bloody Sunday as the pivotal moment in Dugdale’s evolution from left-wing activist to violent revolutionary. Lawlor describes it as “a turning point – a defining moment of her militancy, a moment that crystallized many of her thoughts”. Everything that happened next in Dugdale’s wild and unscrupulous journey seems to spring from her rage and indignation at that single terrible event.

In June 1973, on Heaton’s instructions, Dugdale and three other people broke into her family home in Devon while her parents were away and stole valuable paintings, art objects, antiques and silver. For some reason, Dugdale thought it a good idea to hide the stolen goods at her former lover Peter Ady’s house in Oxford, who immediately informed Dugdale’s parents. At the trial that followed, Dugdale dramatically expressed her love for her father, but told him: “I hate everything you stand for.” She was given a two-year suspended sentence, while Heaton, who had no direct involvement in the robbery, was jailed for six years.

Photo: YouTube

“He usually wears dirty and untidy looking suede pants and jackets”

Later that year, she met and fell in love with Eddie Gallagher, the wildly impulsive IRA volunteer who somehow had permission to operate independently of the organization’s central command.

Her commitment to the cause of Irish republicanism deepened dramatically and, in January 1974, along with another IRA member, they carried out the daring helicopter hijacking in County Donegal, forcing the civilian pilot to fly their deadly cargo across the border to Streiban .

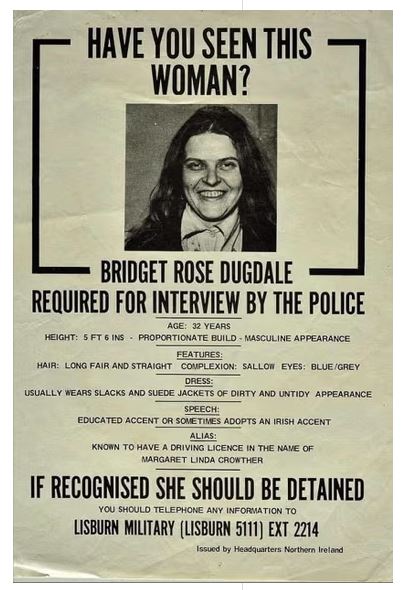

The aerial bombing mission ended in chaos: one bag of explosives fell into a nearby river and the other failed to detonate on the barracks grounds. In the wake of the attack, a wanted poster featuring a smiling Dugdale appeared across Northern Ireland, with her description reading: “Usually wearing trousers and suede jackets with a dirty and untidy appearance.”

The 19 paintings were found in the back of her car

In April 1974, the emboldened couple led the successful art raid on Russborough House, but after a nationwide manhunt, Dugdale was arrested at a country house in west Cork and the 19 paintings were found in the back of her car. At one point he had threatened to burn them if the gang’s demands for the release of IRA prisoners, specifically the Price brothers, were not met.

At the time, Dolours and Marian Price, who had been convicted of IRA bombings in England, were on hunger strike in Brixton Prison. Dugdale’s extravagant gesture of support was somewhat undermined by a public statement from the sisters’ father, Albert, urging her not to destroy the paintings as that would be a sin.

Even in prison and pregnant with Gallagher’s child, Dugdale proved a nuisance to the security forces in Ireland. On 3 October 1975, she made headlines again when Gallagher and another IRA volunteer, Marion Coyle, kidnapped a Dutch industrialist, Tiede Herrema, from his home in Limerick, and issued a statement calling for her own release in exchange for Herrema’s safety.

Photo: YouTube

The heroin problem

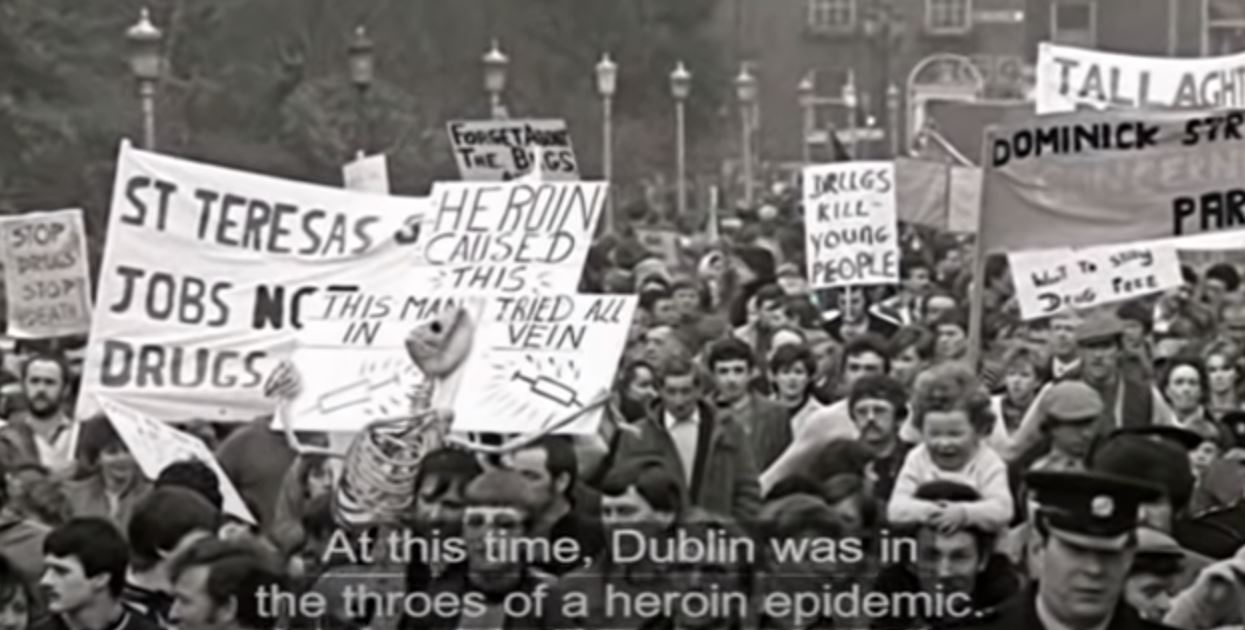

On her release, Dugdale threw herself into a campaign by a controversial organization called Concerned Parents Against Drugs, which aimed to directly combat the burgeoning heroin problem in Dublin city center in the early 1990s. 80’s. Often using IRA members as executioners, they marched into the homes of known drug dealers and forced them to leave.

In O’Driscoll’s book, a woman who looked after Dugdale’s son recalls seeing Dugdale speak at an anti-drugs rally and thinking, “Thank God I’m not a drug dealer or drug user, having to deal with that woman.” .

There is a clear sense, in all this, that Rose Dugdale saw her life as a series of risky, rebellious episodes, designed to prove her reliability and devotion to a cause she embraced with a kind of reborn fanaticism.

“I had to struggle with the idea of killing people”

“If you come from England, you’re always a Brit,” she said in an interview on Irish television in 2012, “and if you come from my background, it was no wonder they found it difficult not to take me as a member of the republican movement.”

In order to be accepted, she had to wage a long war with her own country, class and origin. “I had to struggle with the idea of killing people, but, at the end of the day, it’s the only way to deal with them,” she later said of the decision that would dramatically redefine her. “Essentially, this was military action that had a chance to succeed. In my mind, there was no doubt about it.”

As Sean O’Driscoll points out, this commitment cost her her family, her friends and a lifetime of privilege and security. It also claimed the lives of countless others. For all this, Rose Dugdale seems, even in old age, to be as devoted as ever to the cause she pursued with singular, total devotion.

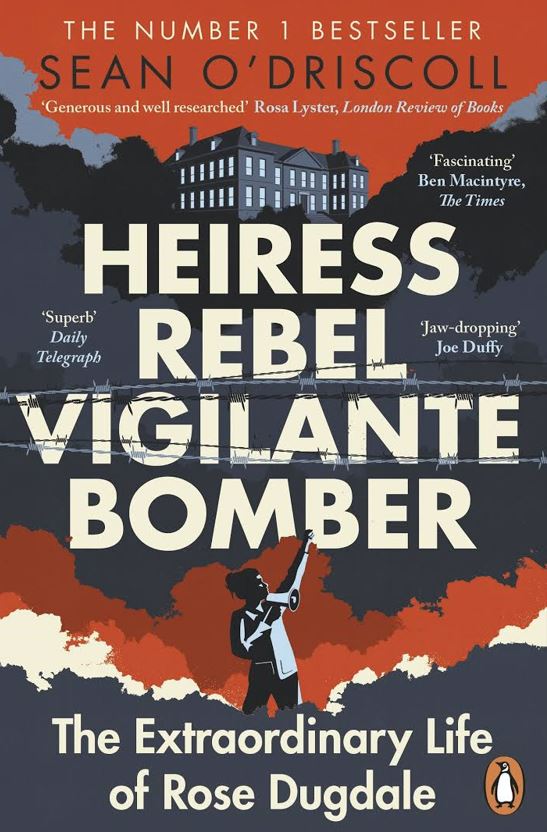

Heiress, Rebel, Avenger, Bomber: The Incredible Life of Rose Dugdale by Sean O’Driscoll is published by Penguin.

The best day of her life

Once, O’Driscoll says, he asked her what the best day of her life was, assuming she would choose the day her son was born. Instead, he replied that it was the day of the Strabane bombing. “For her, I guess, it was the moment of no return.”

He also recalls an enlightening moment when, as part of his research, he visited the National Military Museum in Chelsea, where, to his surprise, in a section dedicated to the riots is one of the biscuit launchers that Dugdale helped develop.

“From the window I realized I could see her family home, this beautiful house with a park in front and the Duke of York’s military base next door. It made me wonder again why anyone would reject that kind of upbringing for a life of such extreme radicalism. Her dedication definitely took her to another level.”

*The movie “Baltimore” is in cinemas in the UK and Ireland from 22 March.

*”Heiress, Rebel, Avenger, Bomber: The Incredible Life of Rose Dugdale” by Sean O’Driscoll is published by Penguin.

*With data from theguardian.com

#enigma #Rose #Dugdale #debutante #Britain #Irelands #No1 #wanted #terrorist

2024-03-15 09:10:02

:quality(75)/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/elcomercio/DUMPRD6AKNHC5NP6J2THITP6PU.jpeg?w=150&resize=150,150&ssl=1)